I Never Want to Write About Deepfake Sexual Abuse Again

Why nobody’s solved this horrifying problem—and how you can help

Welcome to The Wayfinder, your guide to our toxic information environment. Have a personal question about disinformation, online safety, or digital harms? Submit it to my advice column here!

I’ve been writing about non-consensual image abuse for nine years.

Nine years of ruffling feathers, pointing out that half of the world’s population was suffering while the other side spent their time making policy around harms that hadn’t yet happened.

Nine years of being told the systematic objectification of women online was the domain of gender equality organizations, not the governments that represented them or the tech companies that made it possible.

Nine years of being told that the so-called speech rights of anonymous men who want to undress us and insert us into sexual situations we never consented to are more important than our bodily autonomy, our privacy, our personhood.

Nine years of profound disappointment that deepened this week as governments around the world finally seemed to recognize the nature of the problem—all it took was thousands of women, girls, and men (!) per hour being abused by Elon Musk’s bangified chatbot, Grok. Too little, too late.

I am tired of writing piece after piece about deepfake image abuse. It’s complex, but it shouldn’t be intractable for the big brains and big salaries in Silicon Valley. How many more women and girls need to bear their scars to the world before someone with real power in the tech industry stands up for us?

A Retrospective

In 2017, I met Svitlana Zalishchuk, then a Member of the Ukrainian Parliament, at a trendy cafe in Kyiv. I was on a reporting trip for my first book, How to Lose the Information War. Zalishchuk had been instrumental in a communications campaign in the Netherlands that I was planning to write about. We were a few minutes—and a glass of wine—deep into our interview when she stopped me. There was something else she wanted to tell me, something that felt urgent to her, something she hadn’t previously shared publicly. Because of her public profile in the heady years after the Euromaidan protests:

Zalishchuk also became a target for a new kind of disinformation. A screenshot began appearing on posts about her speech showing a faked tweet claiming that she had promised to run naked through the streets of Kyiv if the Ukrainian army lost a key battle. To underline the point, the message was accompanied by doctored images purporting to show her totally naked. “It was all intended to discredit me as a personality, to devalue me and what I’m saying,” says Zalishchuk. (Click to read.)

This was before deepfake technology was accessible or convincing, when “cheap fakes”—convincingly edited images—were the worst that a woman in public life might encounter. But as generative AI grew cheaper, more widespread, and more realistic, the problem ballooned:

These images look real, and to the untrained eye, they may as well be. In 2018, investigative journalist and Post contributing columnist Rana Ayyub was targeted with a deepfake porn video that aimed to stifle her. It ended up on millions of cellphones in India, Ayyub ended up in the hospital with anxiety and heart palpitations, and neither the Indian government nor social media networks acted until special rapporteurs from the United Nations intervened and called for Ayyub’s protection. (Gift link.)

Forums where men gave each other pointers on how to convincingly create such images—and Telegram channels where those who were too lazy to learn could buy them—proliferated. I was targeted as part of the widespread public hate campaign against me because of my job in the Biden Administration. When I looked more deeply at the marketplace that had flourished in the absence of regulation, I was disgusted:

Some creators who post in deepfake forums show great concern for their own safety and privacy—in one forum thread that I found, a man is ridiculed for having signed up with a face-swapping app that does not protect user data—but insist that the women they depict do not have those same rights, because they have chosen public career paths. The most chilling page I found lists women who are turning 18 this year; they are removed on their birthdays from “blacklists” that deepfake-forum hosts maintain so they don’t run afoul of laws against child pornography. (Gift link.)

I wasn’t alone. The American Sunlight Project found that one in six women Members of the United States Congress were targeted by deepfake sexual abuse material when we took our research snapshot at the end of 2024. We worked with those targeted to get the material removed, in a grotesque game of Whack-a-Troll that you could play for your whole life and never win. Meanwhile, social media platforms profited from abuse of women and girls all over the world. In September, we discovered that Meta was running thousands of ads for nudifying apps that were defying the European Union’s transparency regulations—and running afoul of the platform’s own rules.

That brings us to the current moment, where Elon Musk is facing widespread public outcry for providing free access to a powerful technology that can violate anyone’s basic rights. His response? He initially made the service available only to paid subscribers. As my former colleagues at the Centre for Information Resilience point out, this could allow X/Grok to more easily track down who is creating illegal content. But these are the same guys who were recently stunned when a bunch of “verified” accounts posing as MAGA influencers turned out to be based almost anywhere but the United States. I’m not holding my breath for a sudden change of heart or self-regulation from the man whose initial reaction to the problem was the ROFL emoji. According to reporting from The Guardian, X continues to allow users to post such content.

Why (Almost) Nobody’s Done Anything About It

After Grok undressed tens of thousands of people (by the most conservative estimates) without their consent, advocates like me were gratified to see countries around the world take serious action against Musk and his companies. (Tech Policy Press has a regularly-updated list of those actions here.)

But why did it take so long to reach the critical mass necessary for action? There are two key reasons: lack of awareness and greed.

Take this gentleman, for example, who had responded to a post I made on Substack outraged Musk would monetize access to Grok’s nudification features:

Unfortunately, this attitude persists among many who don’t understand the problem. Fox’s Jesse Watters (hardly a paragon of tech policy prowess) referred to deepfake sexual abuse as “sexy memes” on his primetime show when the TAKE IT DOWN Act—a bill that criminalized deepfake sexual abuse and required platforms to take down instances of it within 48 hours of victim notification—was included for passage in 2024’s National Defense Authorization Act. Elon Musk, at the time readying himself to slash and burn the US Government, first had a go at the NDAA, getting the bill shunted to the next legislative session. This move benefited him; if TAKE IT DOWN had passed in December 2024, its takedown provisions would have come online in late 2025 or early 2026, and X would have been responsible for the fallout of this scandal. Because of the delay, the law was passed five months later, and the takedown provisions now come online in May. In the meantime, Musk issued a mea culpa from a chatbot and hoped he’d receive a get out of jail free card in return.

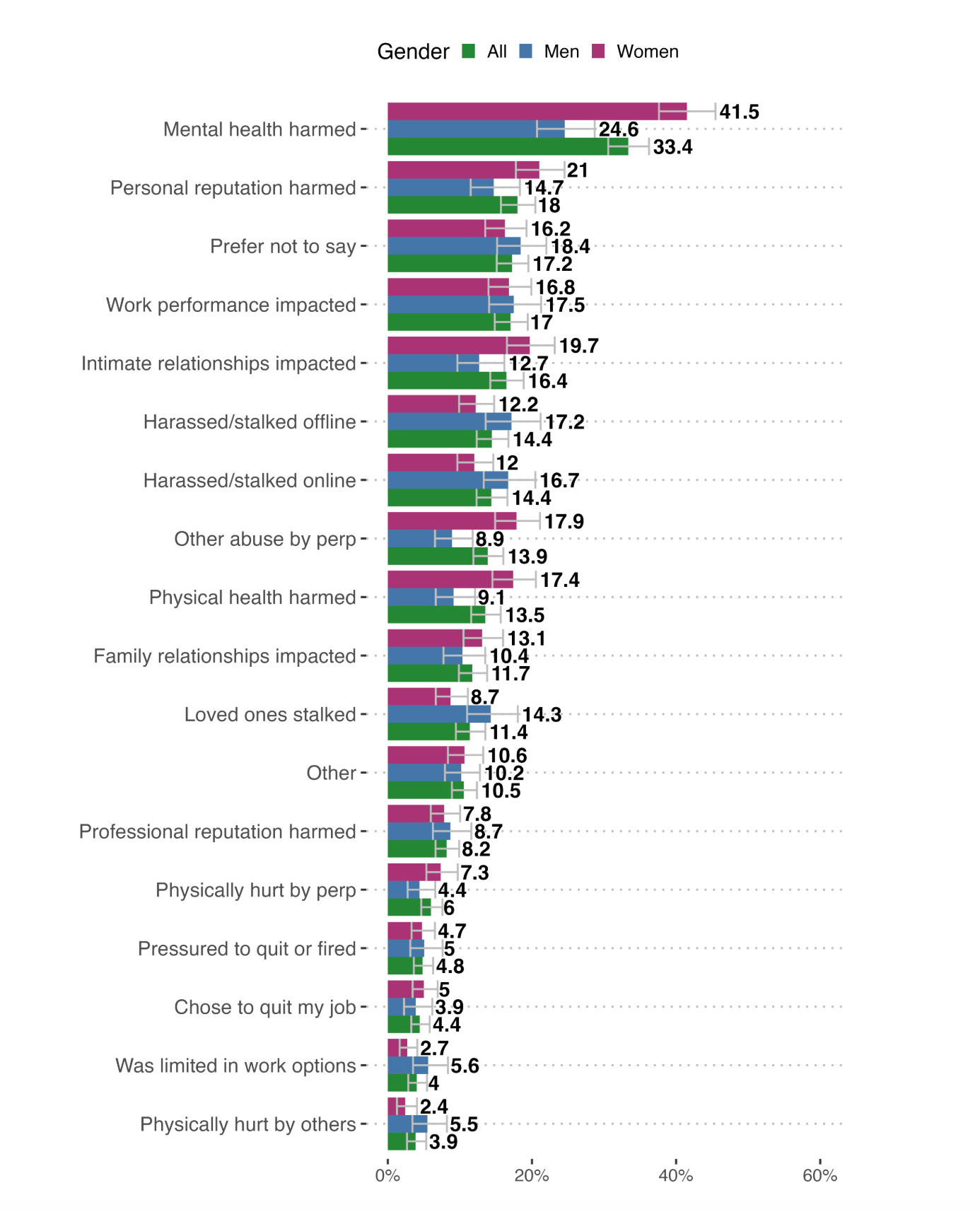

What Watters, and Musk, and this Substack rando don’t understand is that the harm from deepfake sexual abuse is real. Take a look at the impacts reported by targets of image-based sexual abuse (including both deepfakes and authentic images) in a multinational study conducted in 2025:

We shouldn’t need to prove harm to protect our basic rights. If a man can’t undress me on the street without my consent, he can’t do it online, either. Yet that’s exactly what the current paradigm incentivizes and encourages today.

There are some people at the platforms who understand and care about this issue. These are people who want to make a positive difference in the lives of victims, but they’re working against a system that sees us as a cost. Creating policy and taking proactive measures to identify and stop deepfake sexual abuse before it’s created? Responding to takedown requests once victims issue them? Those are expensive propositions.

In the meantime, a lot of companies are making a lot of money on nudification—not just the Groks and the nudifying apps of the world, but the infrastructure that supports them. All of these tools depend on hosting services to keep their websites and apps running. All of them have bank accounts. All of them rely on third-party payment processors like Paypal or Stripe to receive money. Many of them—including Grok—are still available on the Apple and Android app stores. To them, we do not represent bodies that have been violated, but dollars and cents added to their bottom lines.

How You Can Help

You might feel powerless in the face of this disgusting explosion of misogyny. It’s understandable; even if you or someone you love never posts a picture of themselves online, someone can take a photo of you in a high school yearbook, pay a few dollars, and publicly undress and sexualize you.

Shame is still a powerful tool, though, and it might be just what we need to finally wake up the companies that aid and abet the creators of deepfake sexual abuse material. In a moment where the broligarchs and the autocrats are so well-aligned, people power is more important than ever.

Here are a few ways you can use your speech rights to pressure technology companies to take the threat Grok poses seriously:

If you’re an Apple user, ask Apple to remove Grok from their app store here.

If you’re an Android user, ask Google to remove Grok from their app store here.

Contact Microsoft and urge them to end their partnership with Grok.

Complain to Visa and Stripe, which have both partnered with X on payment services.

If you live in the United States, ask your Representative to pass the DEFIANCE Act, which just passed the Senate via voice vote. This bill gives victims a civil right of action to sue deepfake creators. Find your Representative and get their contact information here.

If you live in Europe and see an ad for a nudifying website or app, report it here.

If you have been targeted by deepfake or other image-based sexual abuse, the following resources may help:

StopNCII.org can help you remove sexually explicit images across the internet.

This form allows you to remove sexual content associated with you from Google search results.

The Online Ambulance at StopOnlineHarm.org is a support system for those experiencing online abuse.

Cyber Civil Rights Initiative: offers a safety center that includes a directory of attorneys well-versed in this area.

Bloom is an online platform that can support you in your healing journey.

Together, I hope we’re moving toward a digital future where users’ safety is taken seriously, so this can be my last column on deepfake sexual abuse. 🧭

Did I miss anything? Do you have questions? Leave them in the comments, or submit a more specific question to my online harms advice column. Thanks for reading and being an ally in this fight.

Nina, thank you for this distressing article, complete with action items. FYI, Apple does not have any communication method to request that they removed Grok from the App Store. They intentionally make this action difficult-impossible. I was able to send an email to Microsoft and to Visa.

Thank you for making us all more informed.